One of the enduring myths about Africa is that it was a primitive continent without education or written culture. The best example of this attitude is Hugh Trevor-Roper's comment in 1963 that: "Perhaps in the future there will be some African history to teach. But at present there is none. There is only the history of Europeans in Africa. The rest is darkness."

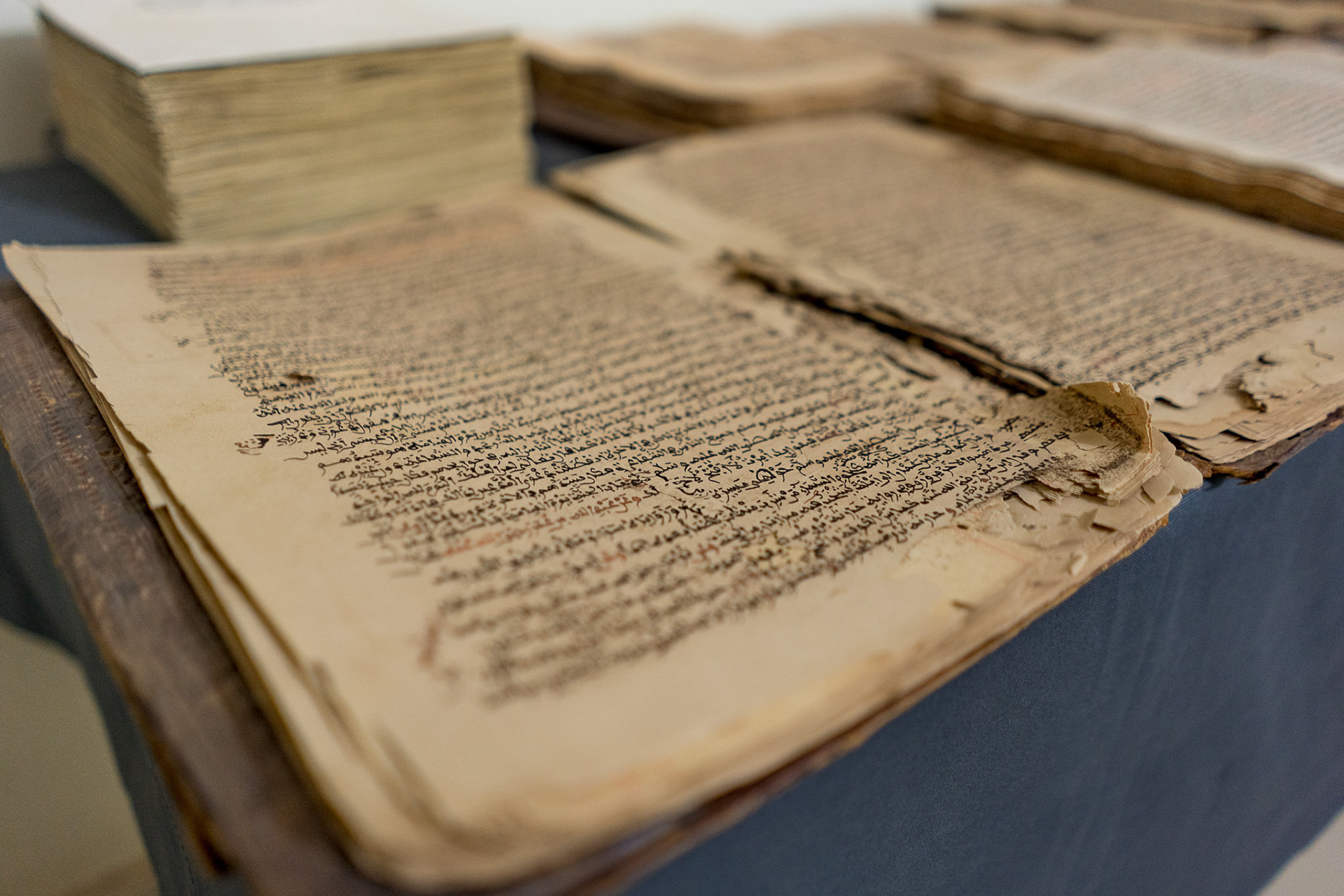

In reality, Africa was a continent of learning, scholarship, and knowledge. One of the centers of knowledge on the continent was the fabled city of Timbuktu. The city reached its peak during the 15th and 16th centuries when its universities drew students and teachers from across Africa and the Middle East. The scholars of Timbuktu wrote thousands of books on topics including religion, science, politics, medicine and diplomacy. The scholars also imported hand-written copies of books written in other parts of the world and the trade in books was one of the city's major activities. These manuscripts ranged from single sheets of paper to entire books. After the city was sacked in 1591 by the Moroccans, many manuscripts were destroyed while others were taken by the great families of Timbuktu and hidden across the region, where they would remain for the next 400 years.

One of the most important modern figures in preserving and sharing Timbuktu's literary heritage is Abdel Kader Haidara, a Timbuktu native and member of one of the city's leading families. The books “The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu” by Joshua Hammer and "The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu" by Charlie English tell the story of Abdel Kader Haidara's work to collect ancient Islamic manuscripts from around Mali, preserve them in museums in Timbuktu, and smuggle the manuscripts to safety in Bamako following the 2012 conquest of the city by Islamist radicals. (See the links at the bottom of this page for more information about Haidara's story.)

Most books and articles end with the successful movement of the manuscripts from Timbuktu to the Malian capital of Bamako. That is far from the end of the story - a great deal of work has been done since 2012 and continues to this day to protect, organize, digitize, and translate the estimated 200,000 - 400,000 manuscripts saved from Timbuktu. The work is being done by the Malian non-governmental organization known as SAVAMA-DCI ("Sauvegarde et Valorization des Manuscripts pour la defense de la Culture Islamique" in French, translated to English as "Association for the Protection and Promotion of Manuscripts and the Defense of Islamic Culture") headed by Abdel Kader Haidara. Different teams from SAVAMA-DCI perform the entire process of cleaning, protecting, indexing, and digitizing the manuscripts.

Cleaning

One of the first steps in the process is to clean the manuscripts to remove dust, mold, insects, or other things that can damage the pages. The preservationists sometimes have to gently peel pages that have stuck together and remove damaged covers. This is precise, delicate work that is done by hand using tools like knives (to remove covers and bindings) and brushes.

Constructing Protective Boxes

While the preservationists are cleaning the manuscripts, another group of people custom-build boxes to protect and store the manuscripts. The boxes are custom-built of acid-free cardboard, linen, and glue to exactly fit the manuscript and ensure that it doesn't move inside the box and damage the delicate pages. Some boxes contain only a single manuscript. Multiple smaller manuscripts are often stored in the same box as it does not make sense to build a box for only a few sheets of paper.

Indexing The Manuscripts

The ultimate goal of the project is not just to physically preserve the manuscripts, but to make them available to researchers and the general public. Accurately indexing the documents is a key step toward reaching that goal.

To do this, a team of indexers reviews each document and records key information, including the number of pages, physical condition of the manuscript, and the collection that it belongs to. They also document the title, author, date, subject, and a synopsis of the manuscript. Since many of the manuscripts are copies of older documents, they also capture information about who copied the document, when, and where.

This process is made more complicated by the fact that the documents are written in a number of different languages. Most are in Arabic, but many of them are written in one of a number of different local languages that have been transliterated using Arabic letters. The indexers need to be fluent in Arabic, but also be able to identify and translate documents written in these other languages.

Because of the importance of this step, all the information is verified by a second person and then translated from Arabic to French so it can be included in different electronic databases.

Digitization

As part of the effort to preserve and share the information in the manuscripts, the center has an active program to capture each of the manuscripts in digital format.

The first step in this process is to number each of the pages. A group of Arabic-speaking staff go through each manuscript to ensure that the pages are in the correct order and then number each page.

After that, the database entry officers create a record in document control system based on the previously-captured index information.

After that, the database entry officers create a record in document control system based on the previously-captured index information.

Finally, a team digitally captures images of each page of the manuscript. On the top floor of the building is a large room full of desks equipped with lights, digital cameras, and computers to photograph each page of the documents. A ruler and gray scale is mounted on each station to provide a reference against which the size and color of the document can be measured. One goal of this step is to minimize the damage to the often very fragile documents. As an example, for documents written on both sides of the pages, they first capture all of the odd-numbered pages - taking a page from the top of the input pile, photographing it, and placing it on top of the scanned pile. They then flip the entire scanned pile and scan each of the even-numbered pages using the same process. This eliminates the need to flip each individual piece of paper.

Storage

The final step of the process is to store the documents so that they are protected from future damage. The temperature- and humidity-controlled storage room at the center's headquarters provides temporary storage before the manuscripts are moved to one of five different locations around Bamako. Each of these locations has a controlled environment to minimize humidity, provide a stable temperature, and physically protect the manuscripts from harm. Ultimately, the group would like to move the manuscripts back to their original museums and owners in Timbuktu, but the current security situation does not allow it.

The Manuscripts

The center has a small room exhibiting some of examples of the different types of manuscripts in the collection. This includes books on Islam, politics, diplomacy, astronomy, math, agriculture, and other topics. Each manuscript ranges from a single sheet of paper to a book hundreds of pages long.

Many of the books have notations in the margins where later owners added their own comments on the information in the original text. These comments provide insight into how ideas changed over time and in different places.

Future Work

The group has made great progress in cleaning, restoring, and digitizing the manuscripts. One of their long-term goals is to translate the documents from Arabic to French and English so that a larger audience can learn from them. This is a huge undertaking that will require significant time and resources to accomplish.

As of 2022, more than 40,000 pages of manuscripts were available on-line through a collaboration between Google Arts & Culture, SAVAMA, and other groups at https://artsandculture.google.com/project/mali-heritage

Learn More

The original efforts to collect and save the manuscripts has been well-documented in different books, articles, and a planned movie. You can find the center's web site (mostly in French) at https://www.savamadci.net.

Some good articles include:

* A review of "The Bad-Ass Librarians" on truthdig.com

* A review of "The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu" on the Spectator web site

* A review of "The Bad-Ass Librarians" from the New York Times

* "The Brave Sage of Timbuktu: Abdel Kader Haidara" on the National Geographic web site.

* An article on the manuscripts on the Guardian web site

* "The Treasures of Timbuktu" on the Smithsonian web site.

* "Preserving the Priceless Manuscripts of Timbuktu" on the PBS web site.

* "After Surviving War, Mali’s Prized Manuscripts Are Now Available Online" on the Hyperallergic web site.